Leaving Islamabad after an interesting few days, we headed north towards China, and the second of the three roads I had really been looking forward to – the Karakorum Highway. First, we battled the city traffic to the hill station of Murree, north-east of the capital; a common getaway for locals escaping the heat. The road winds through verdant alpine forests, running along river valleys and sheer cliffs.

In some places, the roads are lined with suspicious looking plants.

Locals sell rugs, shawls, umbrellas and other random items on the roadside.

Passing further north, we briefly joined a lower section of the Karakorum Highway between Abbottabad and Manshera, sadly at this point just an inter-city highway clogged with traffic. With some relief, we turned off towards the local holiday destination of Naran, soon finding ourselves back on the winding rural roads across scenic countryside.

Any time we stopped for a break or rest, no matter how quiet the spot, within five minutes we would have several car loads of friendly locals stopping, asking us about ourselves, the trip, our impressions of Pakistan, and endless photos and selfies. It was great to engage with such lovely and well-meaning people, but it did wear thin at times when all we wanted was ten minutes to ourselves to have a break from the saddle.

A single night spent in Naran revealed a fascinating town. What we thought would be a sleepy hamlet with a few overnight hotels proved to be an incredibly lively and active place, with dozens of touts on the street trying to get you into their hotel or restaurant – to the point of standing in front of the bike blocking your path while shoving a business card almost into the helmet.

The next morning we proceeded through the alpine valleys that could easily be mistaken for the lower Alps or Pyrenees.

Literally thousands of beehives lined the road, with locals tending dozens at a time, mostly without any protective gear – not even a face net. The honey was being sold in a strange variety of containers including water bottles and jugs.

Waterfalls and small glaciers often abutted the road, with some enterprising locals using the ice to good effect!

Houses here were mostly traditional style, stone structures, sometimes with mud and straw rendered walls but often not. All were very low to the ground, doors often only a metre high. Some villages clung grimly to steeply vertical land.

We passed a small lake, with beautiful green water that was so still it held a perfect (green-tinged) reflection of the sky.

Just east of Chilas, we rejoined the main Karakorum Highway, where it follows the Indus River through a hot and desolate valley – temperatures were nudging 50 degrees at this point.

Chinese money and construction is everywhere, with this being the key trade route from Western China to the Indian Ocean and on to the Middle East and Africa.

As we climbed out of the valley and further north, the temperature mercifully dropped. The road was fantastic smooth blacktop, allowing speedy progress.

At this point, the confluence of the Indus and Gilgit rivers, three of the highest mountain ranges in the world meet – the Himalayas on the right, the Karakorum in the distant centre, and the Hindukush to the left.

We passed a number of police checkpoints, but all were universally friendly and welcoming. The common theme across Pakistan is a concern for how their country is viewed by the West, and that we as valued guests are enjoying a trouble-free stay.

At times, original stretches of the ancient Silk Road can be seen, often just foot or donkey tracks winding across sheer mountain faces.

As the day grew late and the shadows long, we bypassed the administrative hub of Gilgit to push on to the Hunza Valley, renowned as one of the most beautiful places in Pakistan. Looming, snow-capped peaks grew more prominent, particularly Rakaposhi, a 7,800 metre giant.

We settled in for the night in Karimabad, formerly the capital of the nation of Hunza, independent until the 1940s. The ancient village of Baltit and well-preserved fort above it date back to the 13th Century. Deciding to take a rest day here, we wandered through the village towards the fort.

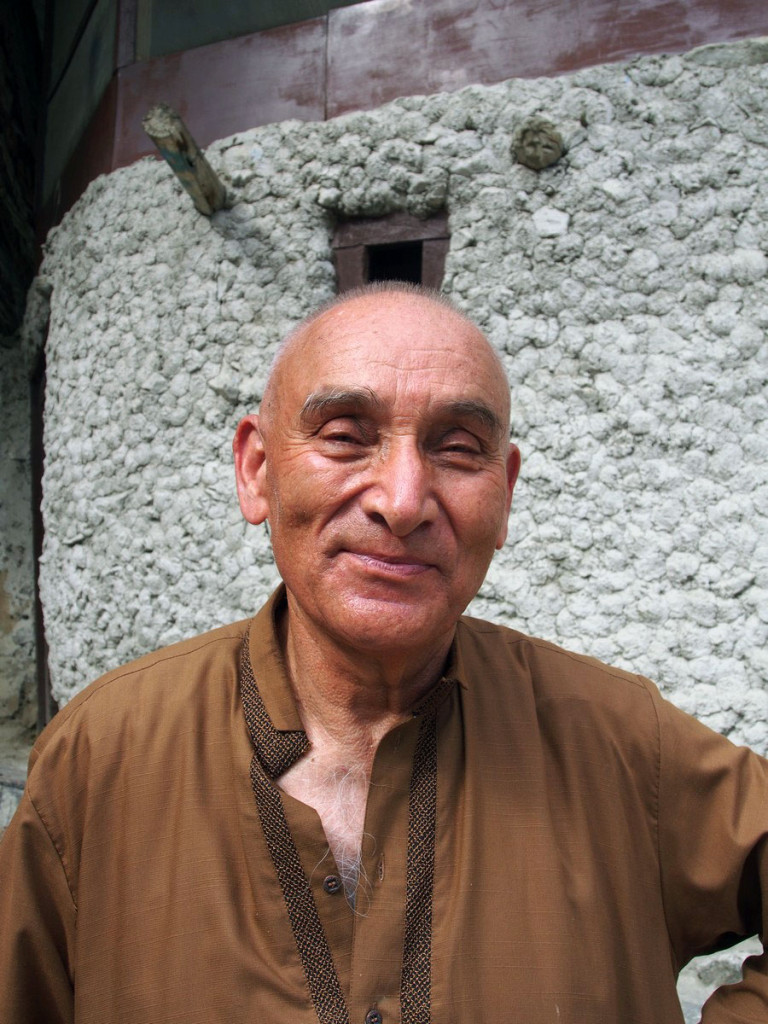

The locals were fascinating, all very friendly and with stories to tell. Although they’re constantly smiling in reality, when posing for photos they put on a serious face.

At the summit of the town stands the fort, a tall, whitewashed structure, with commanding views over the valley and the village.

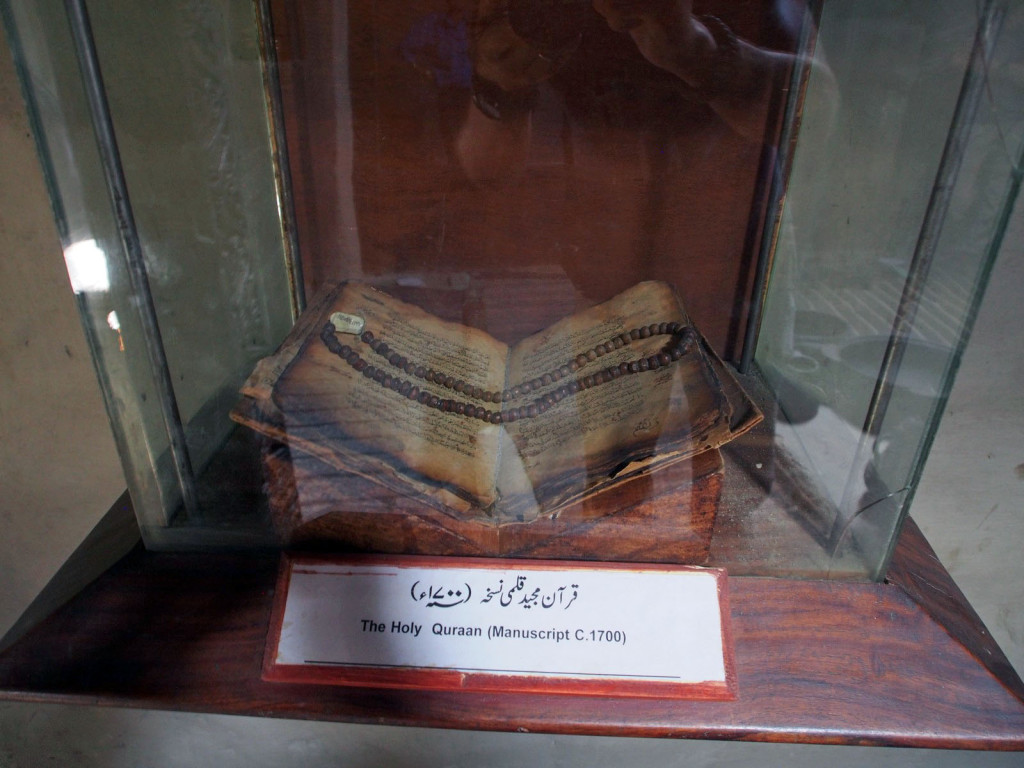

Inside is a mix of doors and beams at odd angles, artefacts from the town’s history, and rooms with the original restored décor. Very interesting and well-preserved, considering they have no government funding, relying solely on ticket sales.

The view from the rooftop and the Mir’s throne is breathtaking.

This cannon, locally made in the 19th Century, apparently caused quite a headache for the British when they attacked – as they were unable to bring their own artillery across the rugged landscape.

Refreshed from a relaxing day, we sipped tea while gazing over the gorgeous mountain scenery, ready to tackle the final 180 kilometres to the border the next day.

Breathtaking Dave, utterly astounding.