Hitting the road again, ever westward, we moved into the empty stretches of the Kyzyl Kum desert. It’s 450 kilometres from Bukhara to Khiva, along a bumpy road lined with back-breaking potholes – although there’s brand new tarmac under construction parallel for much of it.

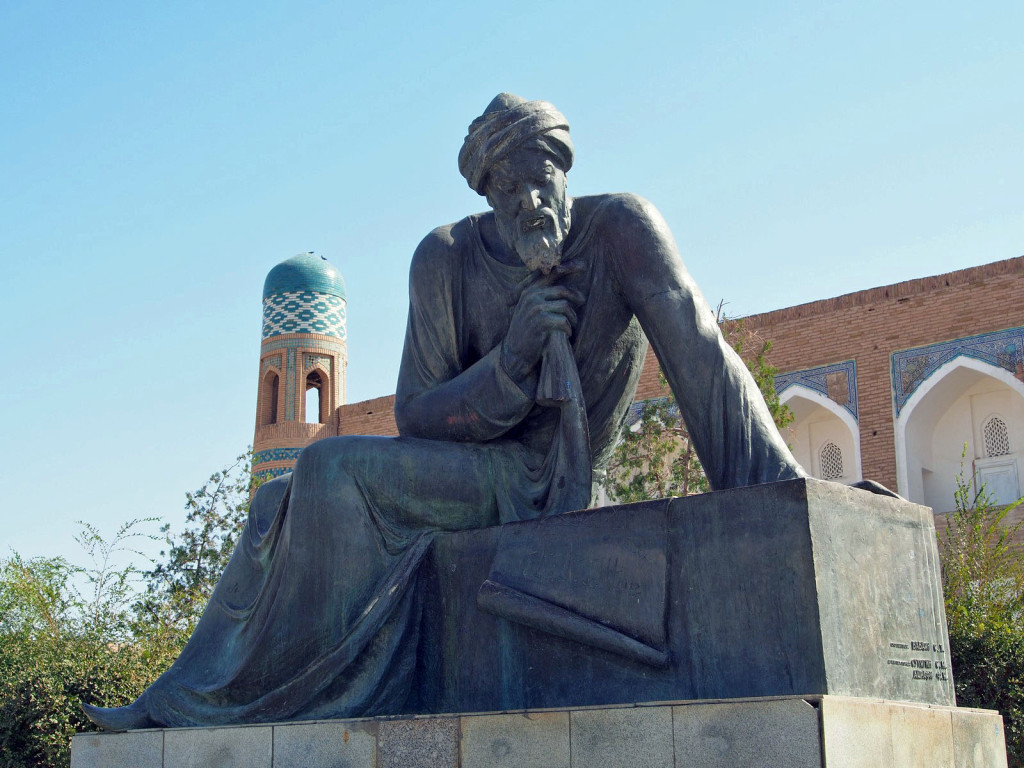

Just as night was falling, we pulled up to the city of Khiva, the third of Uzbekistan’s ‘big three’ sights. After a night of deep, refreshing sleep we tackled the city itself. The old city centre is not ancient, mostly dating from the 18th and 19th Centuries, having been destroyed and rebuilt over millennia, but everything has been preserved and restored as it was before the fall of the Khans in the early 20th Century.

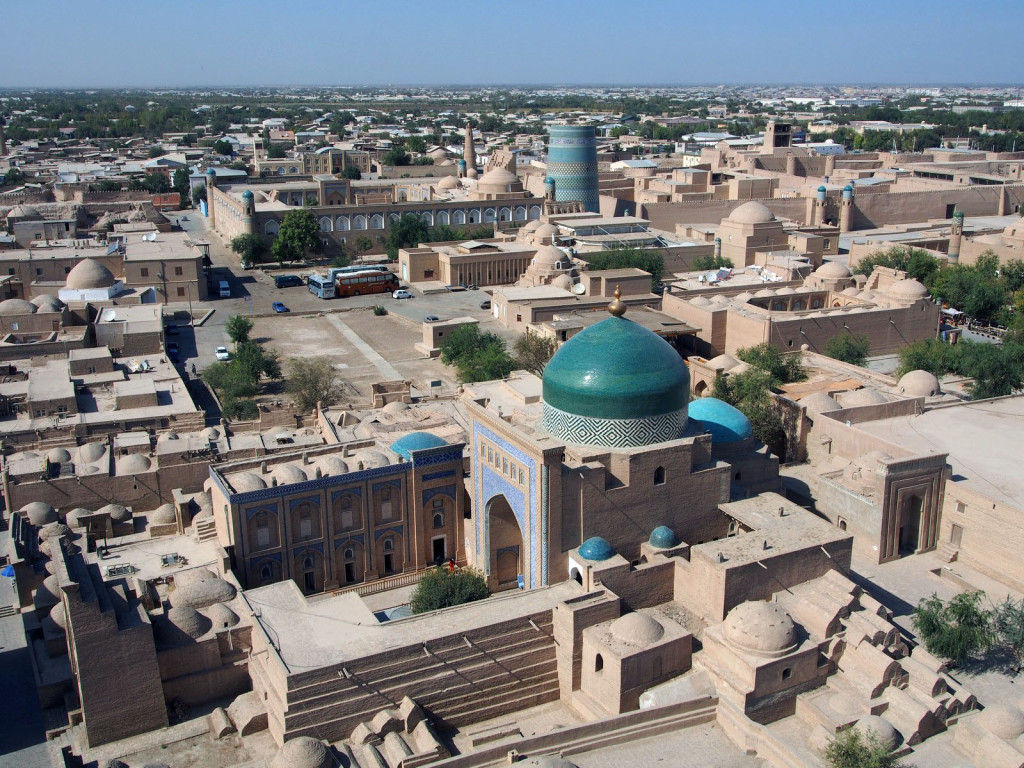

The whole inner city is ringed by 10 metre high mud-brick walls, where there are a few places to clamber up and get your first view of the city – not just the big monuments and medressas, but the traditional local family homes, too.

One of the ‘big’ sights inside is the Tosh Hovli palace, one of two in the city (the other being the walled Ark). A fairly non-descript entrance takes you through servants and administrators rooms before the palace area proper.

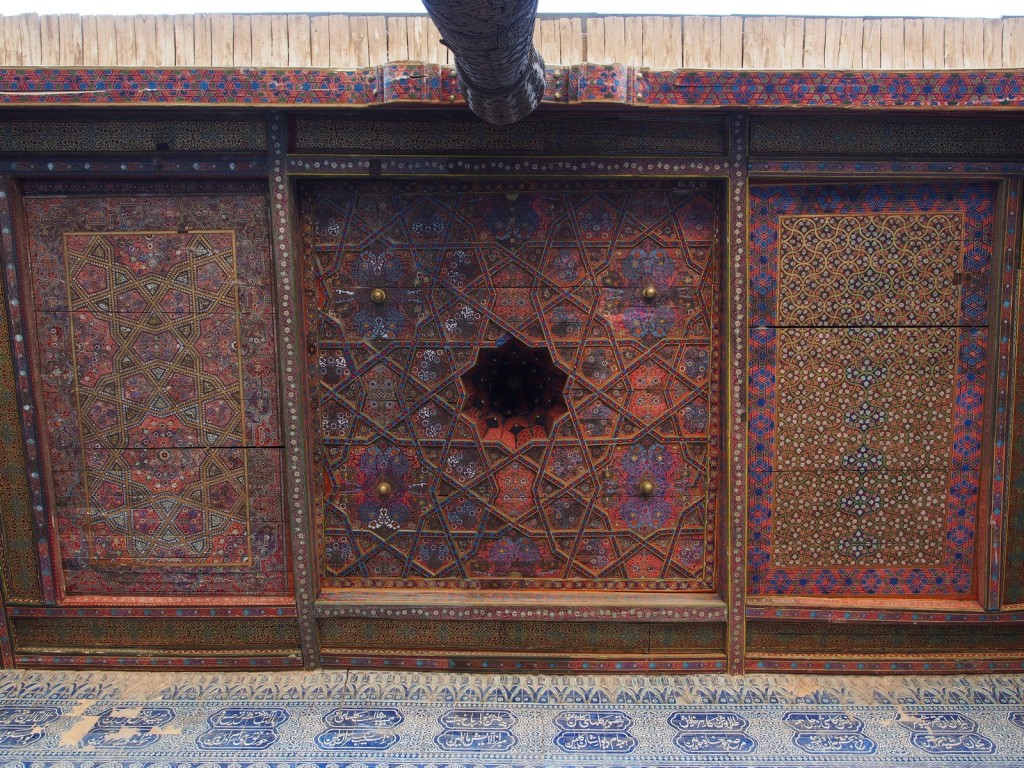

Once you step out into the Khan’s living quarters though, the level of detail and decoration is on-par with anything in Samarkand or Bukhara (albeit showing more damage and wear).

The round dome was used for the Khan’s yurt – which was much easier to keep warm in mid-winter.

It’s easy to forget the present when you’re surrounded so completely by the past – but it always manages to sneak in at the periphery.

One of the most memorable parts of Khiva’s skyline is the Kalta Minor minaret, a squat turquoise-tiled structure. Commissioned by Mohammed Amin Khan in 1851, it is said he wanted to be able to see all the way to Bukhara from it. Construction got as far as 29 metres high before the Khan died, and his successor chose not to bankrupt himself on completing the planned height of 70 metres.

At the other end of the scale of minarets, Khiva is also home to the tallest one in Uzbekistan. The Islom-Hoja mosque and minaret were built in 1910, and it’s possible to climb the thigh-aching 57 metres to the top for a 360 degree panorama.

Just wandering the streets is an excellent way to spend a day, with interesting buildings and alleys around every corner.

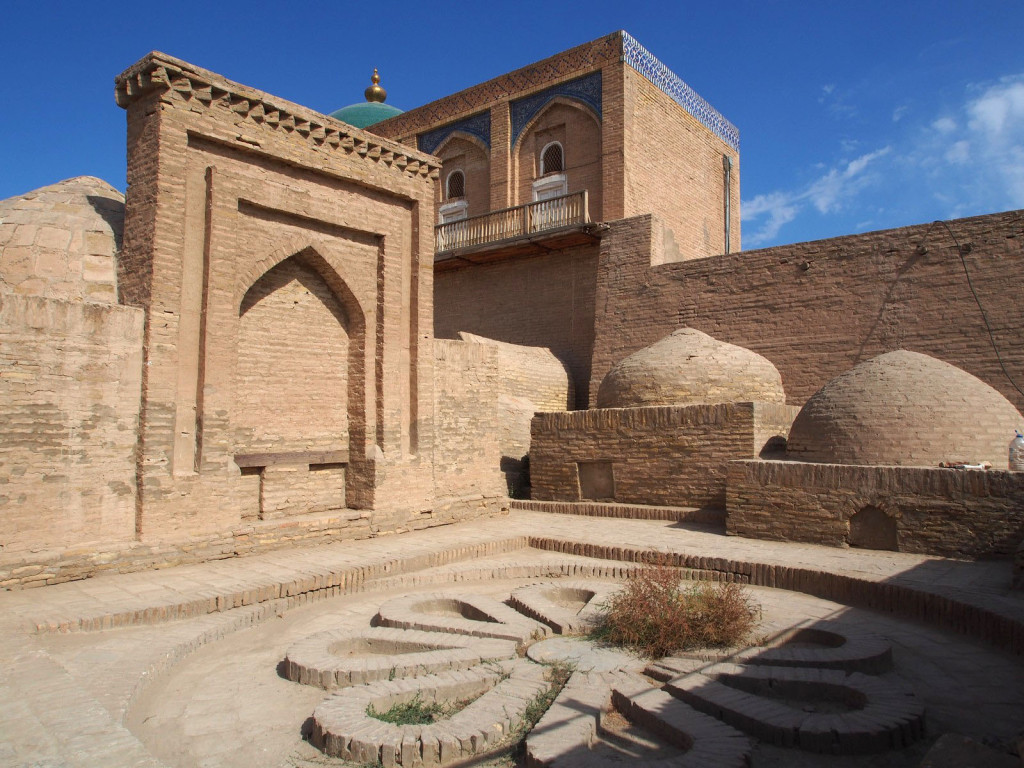

We found this medressa, from 1835, open and almost completely empty – meaning we could explore the upper levels, students’ rooms and more, unlike the much more regulated medressas in Samarkand and Bukhara.

We also found what appeared to be the graveyard, with crypts and low-slung mausoleums scattered at odd heights and angles.

Locals are engaged in either making or selling handicrafts to tourists. Carpentry and carpet-making are popular.

By far our favourite time in Khiva was sunset. It’s possible to buy yourself a beer, climb up the ancient walls and watch the mud-bricks flare to life in hues of yellow and orange as the sun dips below the horizon. We picked two separate spots over two nights, to have a different view each time.

One last comment about Uzbekistan: the money. With one US dollar buying almost 5000 som (on the black market, at least – official rate is less than 3000), and most of the time 1000 som notes are the standard (5000 som notes do exist but they’re rare), you end up with a massive pile of cash when changing money. It’s easy to identify the moneychangers at the bazaar, since they’re all walking around with plastic shopping bags full of bundles of cash.

Would you believe Holly and I took exactly the same photo, but with a US$10 note, not $100, with the stack of Som next to it, back in 1998!

Would you believe Holly and I took exactly the same photo, but with a US$10 note, not $100, with the stack of Som next to it, back in 1998.