A flat, featureless but fast road takes you between Samarkand and Bukhara, second of the ‘big three’ tourist cities in Uzbekistan. Here, much more of the old town (some dating back to Samanid dynasty of the 9th and 10th centuries) remains, in and around the monuments – twisting narrow alleyways and mud-brick houses providing a sense of character and history that was lacking in Samarkand.

The tourist area is centred around the Lyabi-Hauz, a common pool where Bukharans used to wash, drink, and socialise (since water was hard to come by, it wasn’t changed often, resulting in frequent plagues).

There’s a couple of small (at least by Samarkand’s standards) medressas facing the pool.

One is notable for the mosaic image of peacocks clutching lambs, against the Islamic prohibition of depicting live animals.

In a corner of the park is a statue of Hoji Nasruddin, a ‘wise fool’ from Sufi teaching tales.

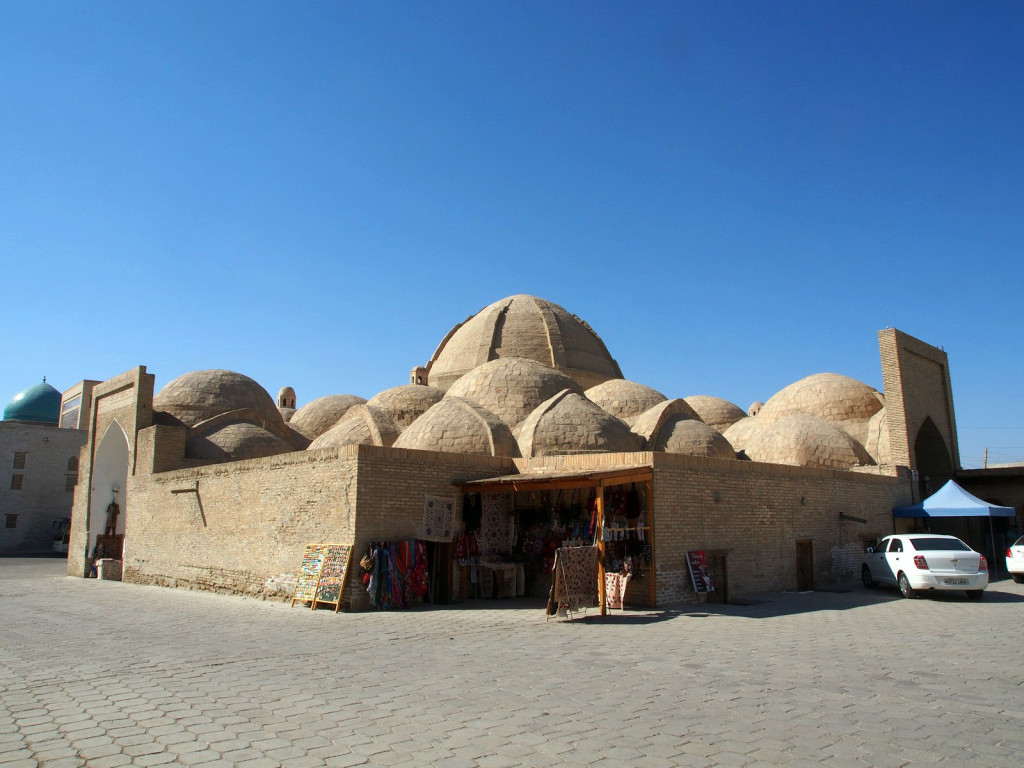

Bukhara is one of the oldest centres of trade on the Silk Road, and has numerous covered bazaars and caravanserais to show for it. They’re still in use, nowadays by souvenir and carpet sellers.

Blacksmithing has long been a speciality here, with numerous master craftsmen forging their own knives – though they’re now made for tourists, as with everything else.

The oldest standing medressa in Central Asia, which served as the model for all others, is the Ulugbek medressa built here in 1417 – just before the one in Samarkand’s Registan. Here though, it’s in significantly poorer condition, with many of the mosaic tiles missing – although it is a much more serene place without all the souvenir shops.

Opposite and facing the Ulugbek medressa is one built by Abdul Aziz Khan in the 16th Century. It’s in generally better condition, with gold leaf decorations on the outside.

Towering over the town, and visible in the skyline from most areas, is the Kalon Minaret. Built in 1147, and reaching 47 metres high, it’s an engineering marvel of the day. It was one of the few structures spared by Genghis Khan when he razed the town in 1220 – although he did destroy the adjoining mosque. The light patches on the minaret are repaired sections damaged by Soviet artillery in 1920.

The Kalon mosque was rebuilt in the 15th Century on the site of the old one, and is said to be able to hold 10,000 worshippers.

Opposite is yet another medressa – the 16th Century Mir-e-Arab. It’s still in use today, so we’re unable to access inside, but the blue domes make for a gorgeous contrast to the brown brick.

The largest structure is the Ark, the old Khan’s fortress and palace. The walls are sufficient for a small town, which is appropriate given the size of the place.

Inside are a number of buildings, including the royal mosque, stables, and apartments.

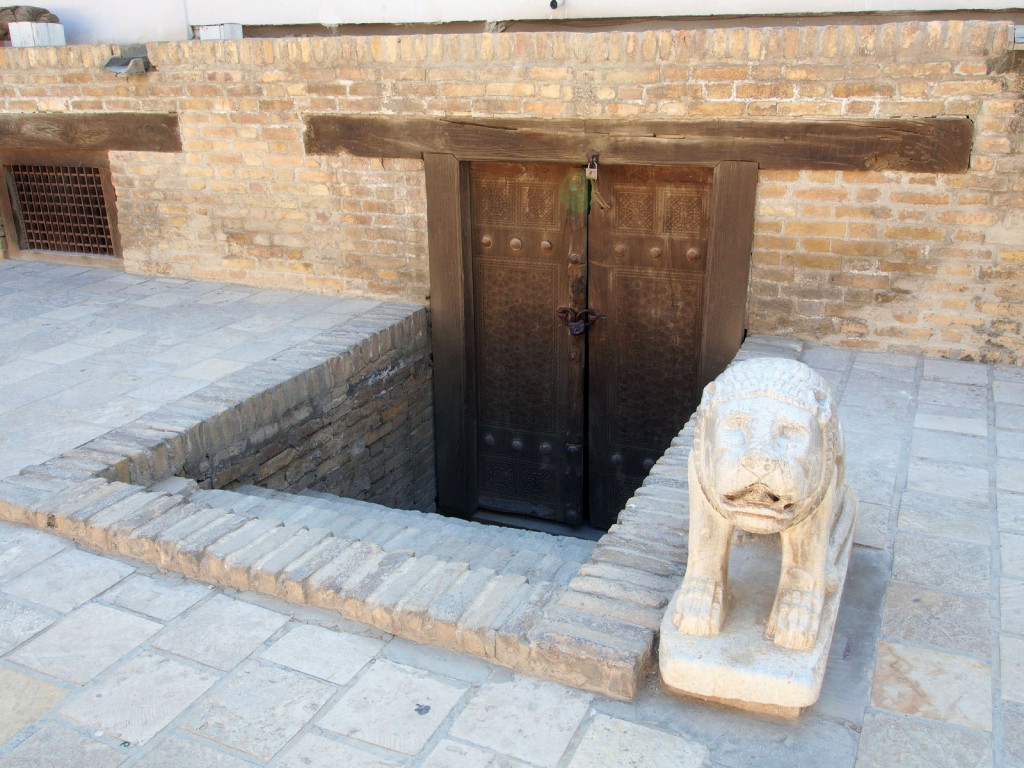

This rather sad-looking chap is guarding the entrance to the treasury.

Outside and around the corner is the Zindon, the Khan’s prison. The one in Bukhara is famous for the ‘bug pit’, a six metre deep hole in the ground filled with rats and scorpions. Its past inhabitants include two unfortunate British officers who were sent as envoys but incurred the wrath of the Khan – one staying there for a number of years before being executed.

The oldest standing structure in the city is the mausoleum of Ismail Samani, the founder of the Samanid dynasty – it dates back to 905AD. It was during the Samanid era that Bukhara was at its most prosperous, becoming a commercial and intellectual centre – earning the nickname ‘the pillar of Islam’. It’s surprisingly small inside, due to the two metre thick mud-brick walls (that are the reason it has survived the ages so well) but the architects managed to create intricate patterns and designs just by the arrangement of the bricks.

One of the most appealing things about Bukhara is not any particular monument in itself, but the ancient alleyways and cityscape you wander through. Unlike Samarkand, where you’re ushered from sight to sight along manicured gardens and perfect pavements, this is a living city that has grown and changed organically over thousands of years.

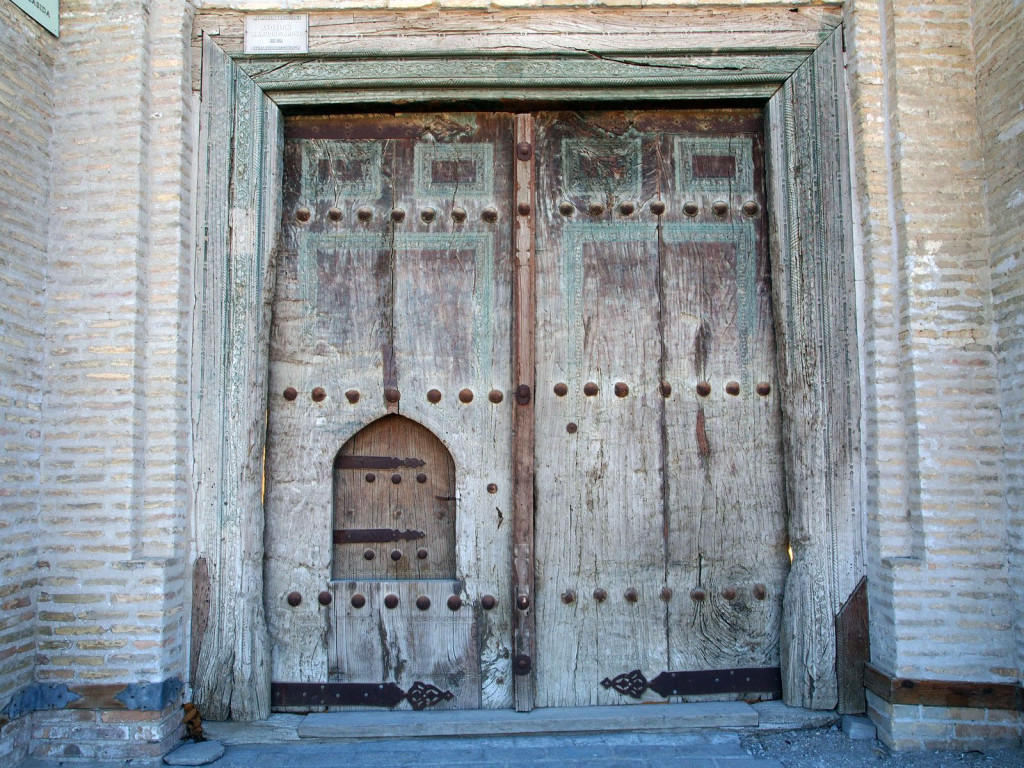

As with Varanasi, some of the most interesting details in an ancient city are the doors.

Tucked away in a residential square is Chor Minor, a small gatehouse for a medressa that no longer exists.

We finished our time in Bukhara by hunting down petrol for the bikes – almost an impossible task. Although there are dozens of service stations, almost every single one is closed, with typically only one or two per city open. It’s easy to tell which is open, by the literally hundreds of vehicles queuing out the front. Fortunately, bikes can skip the queue and ride straight to the pump – because they’re used to local scooters etc only taking a few litres at a time. It would have been a bit of a shock when our bikes swallowed more than 50 litres, more than half the cars there!