We entered Uzbekistan, taking a few hours at the border for a detailed (but not over-the-top like China) search on the Uzbek side. Once free, we made our way through the rolling hills. Cotton is the staple crop here, although its thirst makes it a poor match for the dry landscape.

After a brief overnight stop, we rolled into the town of Shakhrisabz, and into the shadow of Tamerlane, the 14th Century Timurid emperor who conquered most of Central Asia, Persia and made campaigns into Russia, Turkey, China, and further afield. Here was his home town, and a few of the old monuments still stand. Sadly, the place bore closer resemblance to a construction site than a place of history – all the surrounding parts of the old town that once nestled between the monuments had been demolished to make way for a Disneyland-style park, complete with fountains, pavilions and a multitude of souvenir shops.

There’s a modest sized mosque built by Tamerlane, with some of the trademark blue mosaic work, and intricate murals inside.

The nearby mausoleums of some of Tamerlane’s family were undergoing restoration that more resembled recreation – it was very heavy-handed.

The biggest attraction here, both literally and figuratively, is the old archway to Tamerlane’s summer palace, Ak-Saray. Although the span of the archway collapsed around 200 years ago, the remains are hugely impressive.

Finally, it was time to cross the last low mountain range to the fabled city of Samarkand, where the local kids took a shine to the bikes as we were checking in to our guesthouse.

Samarkand was the Tamerlane’s capital, and he transformed it into the jewel of his empire. Vast, intricately detailed buildings abound, although sadly the Disney-fication we saw underway in Shakhrisabz has already happened here – with many parts of the old city walled off and hidden from tourists’ view.

Still, the big attractions are undeniably impressive. We started with the Bibi Khanym Mosque, named for Tamerlane’s Chinese wife. Legend has it she commissioned it as a surprise while he was away campaigning, but the architect fell in love with her and refused to finish it until he could give her a kiss – unfortunately it left a mark that Tamerlane saw on his return, and thus ordered all women to wear veils so as to avoid temptation.

As with most Timurid structures, there’s a gate in front that’s as large as the actual building, and it’s flanked by two smaller dome-topped structures.

Getting behind the scenes though, and the damage accumulated over centuries of warfare, earthquakes and aging is evident – although much of the façade has been restored, there’s still significant structural damage.

Just across the road is Bibi Khanym’s own mausoleum, with the trademark blue dome.

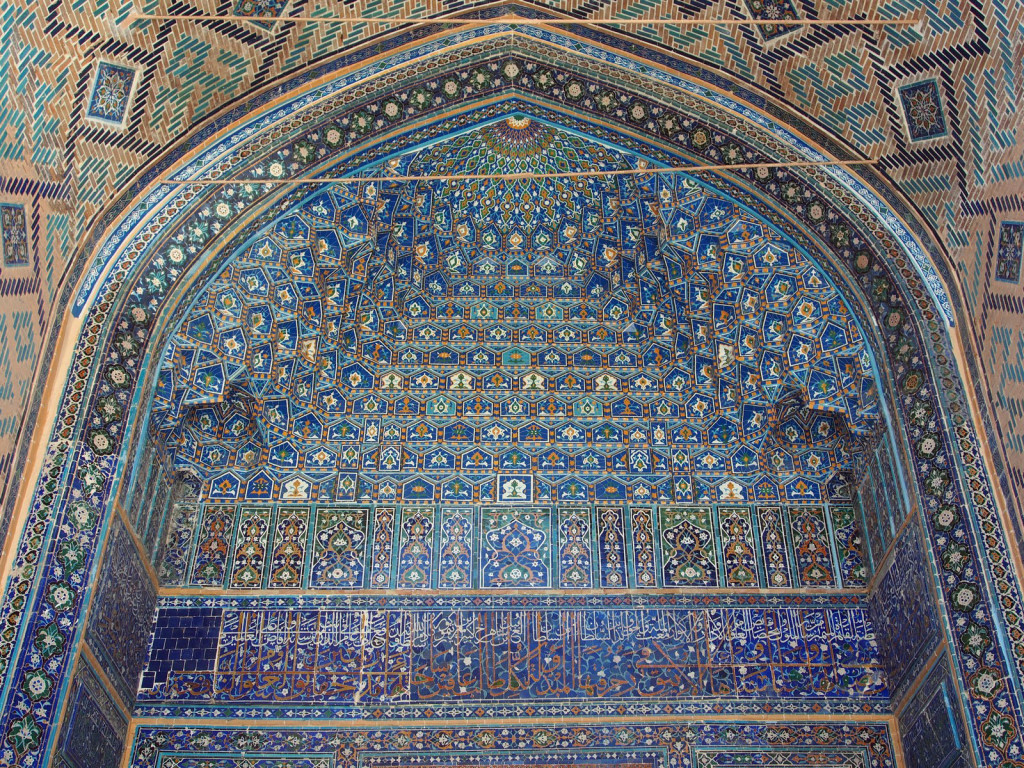

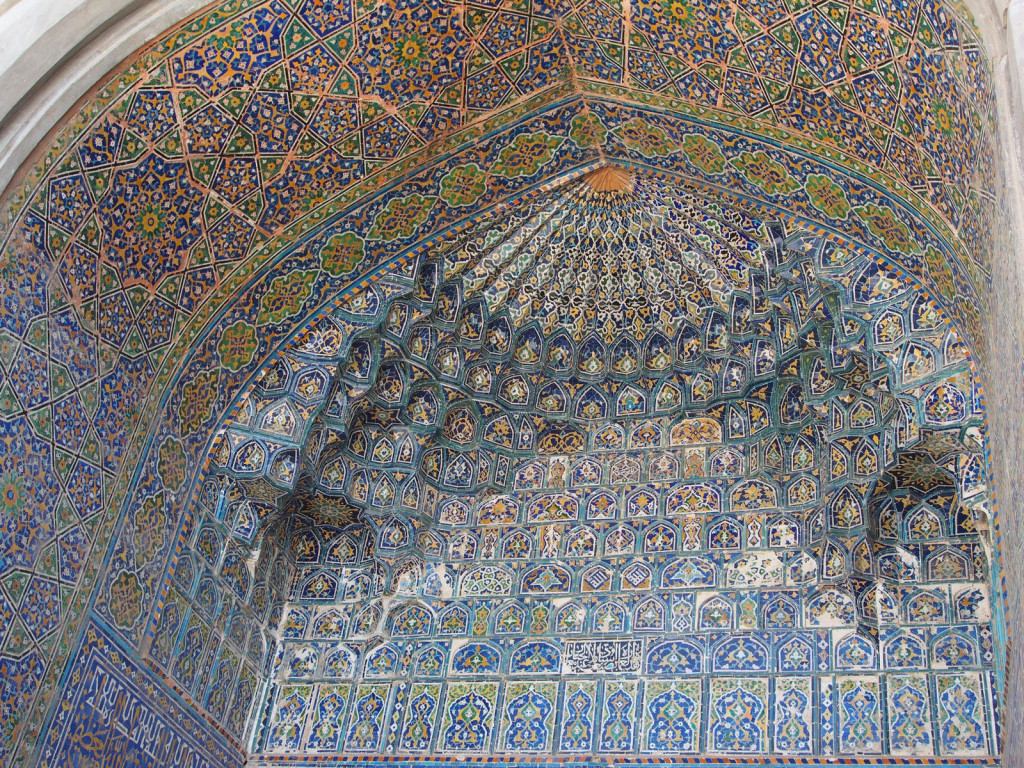

Our next stop was the Shohi-Zinda, the street of mausoleums. Surrounding around the holiest of the tombs, that of a cousin of the Prophet Mohammed who first brought Islam to Central Asia, the series of small monuments becomes more impressive as you get further along.

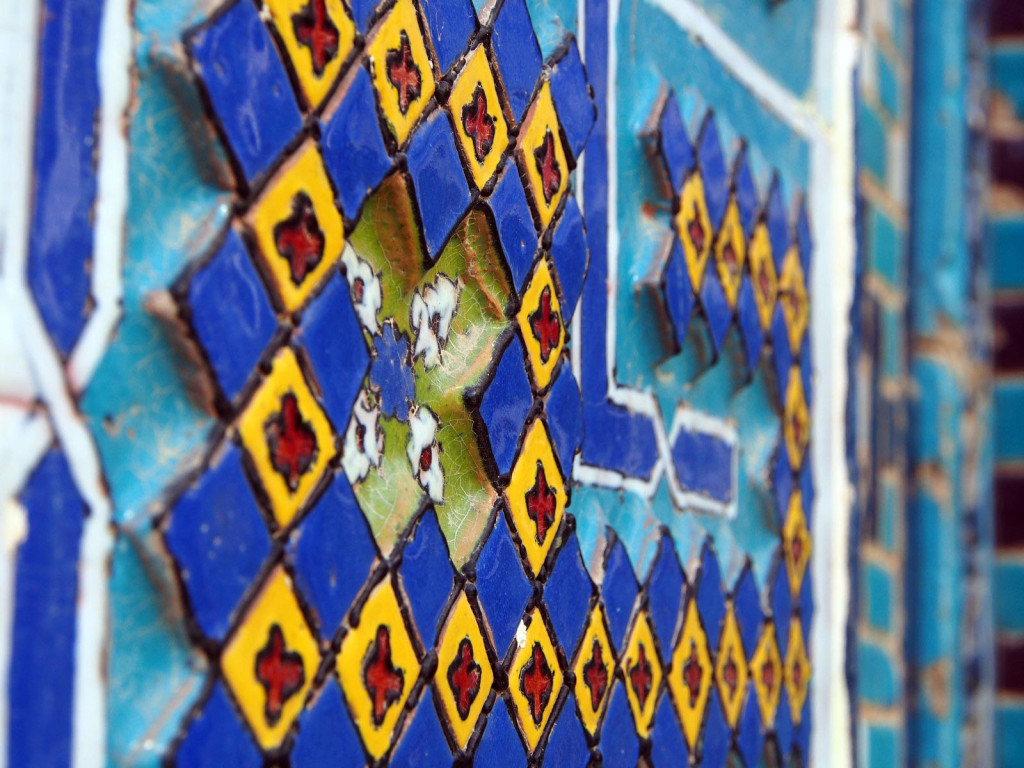

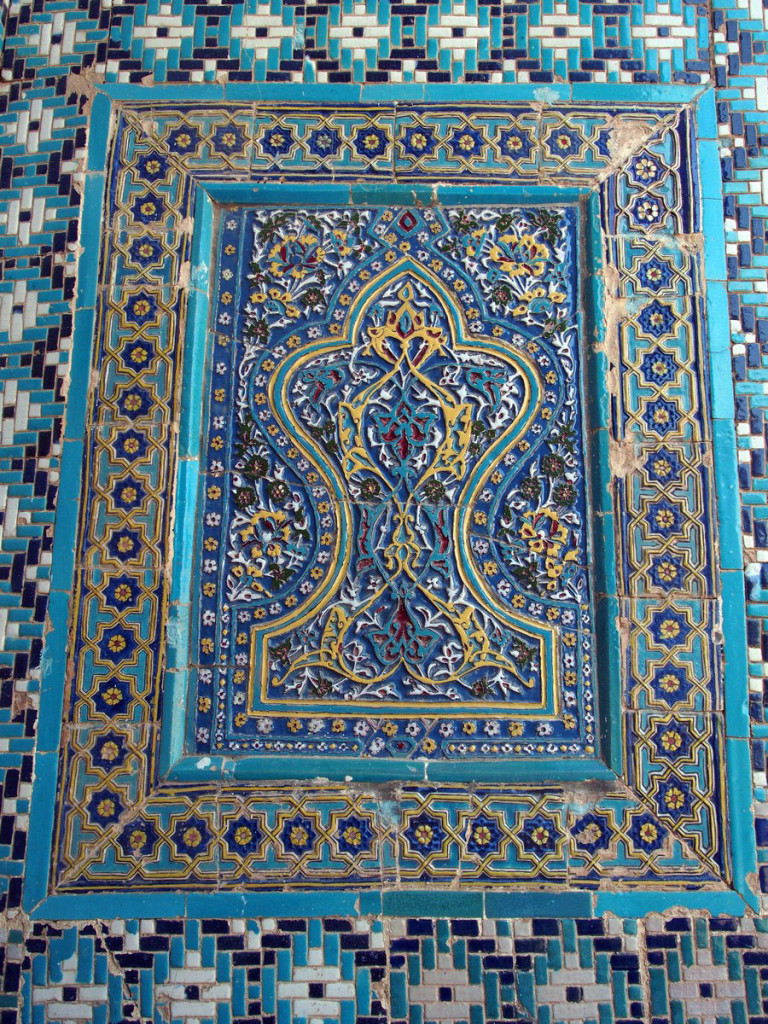

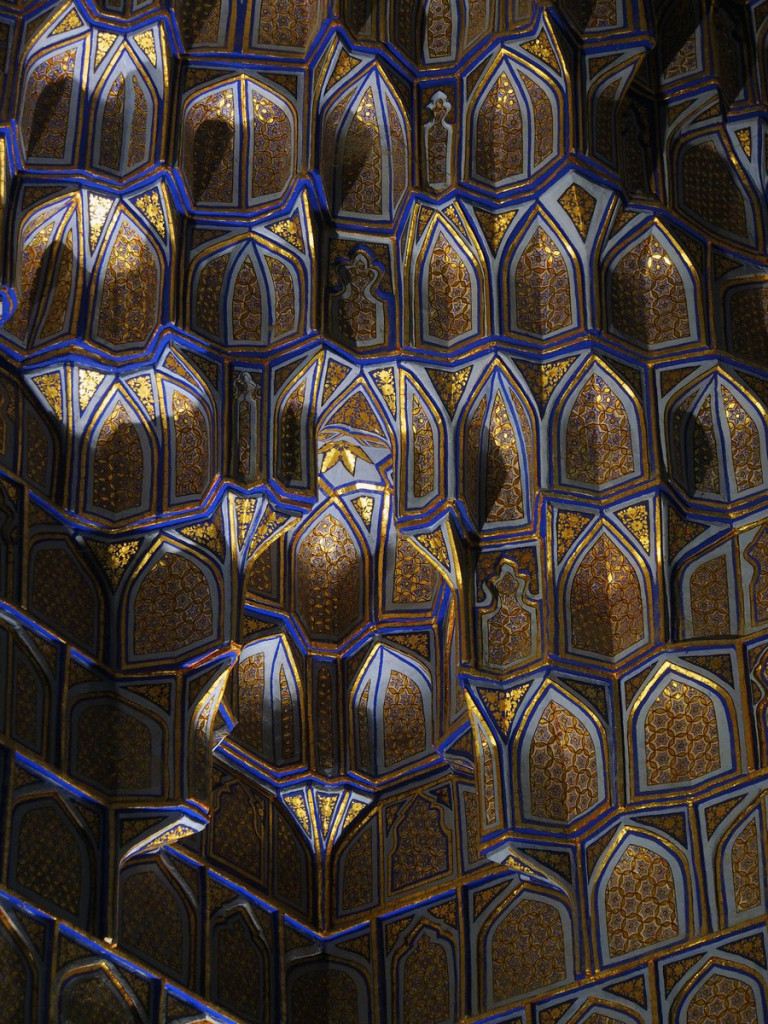

They’re known for having some of the most detailed and elaborate mosaic work in the region.

Sometimes the interiors were spartan and plain, but sometimes they were even more richly decorated than the outside.

Perhaps the most impressive sight in all of Central Asia is the Registan, the central square of the ancient city, around which stand a group of three medressas (Islamic schools) dating from the 15th and 17th Centuries.

Although they follow the same model, each of the buildings has their own quirks and character. The one on the left is the original, the Ulugbek Medressa, built by Tamerlane’s grandson between 1417-1420.

Inside, what were once the students’ rooms are now full of souvenir shops, all selling the same dozen or so items. The gorgeous mosaics do however continue on almost every surface.

We got a chance to climb up one of the minarets and have a view over the rest of the Registan, and the surrounding city – including the Bibi Khanym mosque in the distance.

Most of the tilework and facades have been heavily restored (or perhaps more accurately ‘recreated’) but there are still patches where the original tilework can be seen.

Everywhere near the grand monuments in Uzbekistan are photographers leading newlywed couples, both in traditional and more western-style dress.

Opposite the Ulukbek medressa is the Sher Dor medressa, built almost two centuries later, but copying the style of the original. Most distinctive is the images of lions (who look more like tigers) on the main façade – contravening the Islamic prohibition on depicting animals.

Inside, there is far more damage and restoration works are still underway – but the souvenir shops are still in residence.

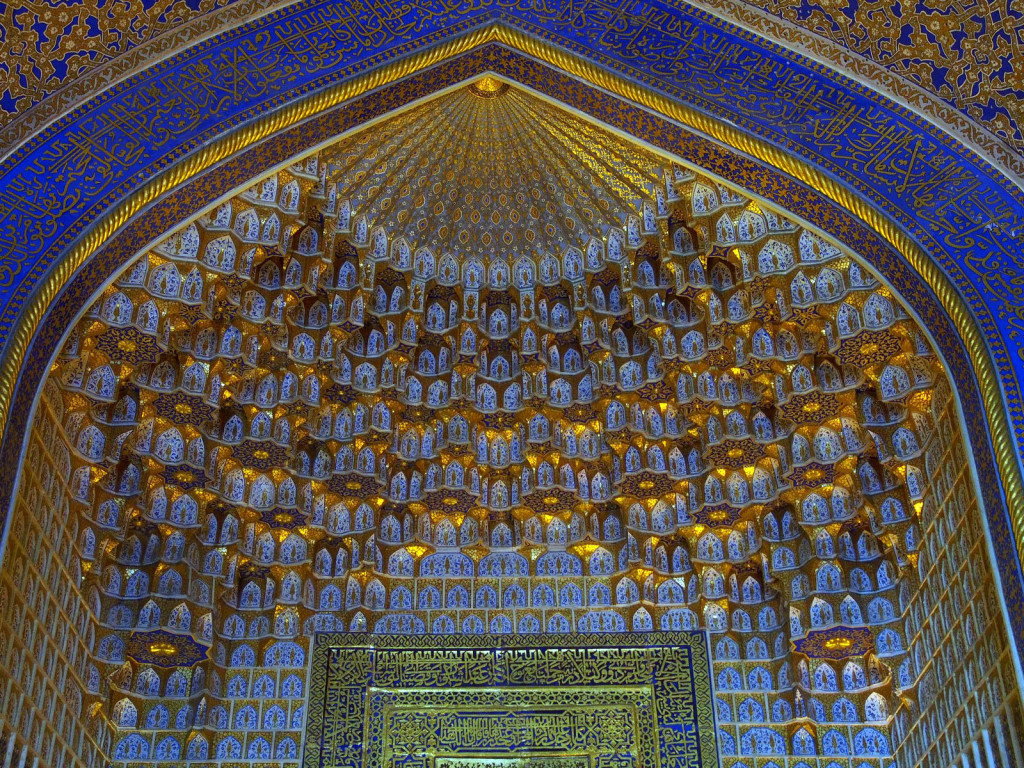

The third of the three medressas, in the centre, is the Tillya Kori, also dating from the 17th Century.

The most famous feature here is the gold-encrusted mosque on the west side – the blue dome that’s offset to the left in the exterior pictures.

Our final grand monument was the Gur-e-Amir, Tamerlane’s own mausoleum. He had intended to be buried at Shakhrisabz, but died in winter when the passes were snowed in, so was interred here instead. For such a grand conqueror, it’s a fairly modest structure.

Inside the gleaming golden crypt, originally built for his mentor, lies sarcophagi for Tamerlane, his sons Shah Rukh and Miran Shah, his grandson Ulugbek, and several others. The dark green (almost black) one in the centre is Tamerlane’s, a solid block of jade.

The monuments become even more impressive by night, the mosaics gleaming under floodlights.

Finally, as we bade farewell to Samarkand, we couldn’t resist stopping in front of the monuments for one last snapshot.

The photos of Samarkand are wonderful! They recall for me the happy time I had there with Holly.