Leaving Siem Riep and the glorious temples of Angkor Wat behind, we hit the road to cover the 320km to Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia. The first half of the road was in good condition, and we made good time. The second half, however, was a nightmare. Constant roadworks, potholes, lane closures, and contraflows. Worst of all was the dust, as bad as in outback Australia. Trucks thundering past in either direction would result in almost total whiteout, leaving you relying on brake lights and instinct to avoid issues. It’s surprisingly bad, considering this is one of the key roads linking one of the largest towns in the country to the capital.

Cambodian drivers are the worst I have encountered so far – they have no concern whatsoever for the direction of traffic or right of way, to an extent only seen so far in Javanese bus drivers – fortunately the traffic density is far less than Java. Particularly when turning across in front of you, they will just plough through and expect you to brake and avoid them. Also complicating matters is the switch in road flow – they drive on the right side here, and it takes a little bit of brain-rewiring to get used to that.

Once we arrived in Phnom Penh we lodged our passports to get the Myanmar visa. Normally a three day turnaround, we thought by arriving on Tuesday we’d have them back Friday, and leave the capital over the weekend. Well, it didn’t work out that way – Friday is a public holiday, so the embassy is closed, meaning we have to wait until Monday. While working out how to escape the city and get back for our passports, we explored a little.

As with everywhere in the world, there are the rich parts of town, and the poor parts. The rich parts have a distinctly European feeling about them, while the poorer parts are classic Southeast Asia.

There’s a messy, if sadly all too common approach to electricity.

The city lies at the confluence of the Mekong and Sap Rivers, which dominate everyday life. Even here in the polluted city, fishermen ply their trade.

Along with stuffing ourselves full of delicious Khmer-French cuisine, we took the time to see a traditional dance show.

It is impossible to go to Cambodia and not notice the scars the country and the people bear from the Khmer Rouge. After winning the civil war in 1975, Pol Pot instituted a radical agrarian communist ideology, literally emptying all cities into the countryside and forcing people to work on communal farms – all while committing a genocide against his own people. Between mass famine, forced labour, the complete dismantling of all healthcare and education, and the brutal executions, it is estimated around 2 million Cambodians died before the Vietnamese invaded and toppled the regime in 1979. It took less than four years for one third of the population to be killed, along with the near total destruction of all administrative and community structures.

Warning: while nothing written or pictured below is ‘graphic’, some may find it disturbing. You have been warned.

One of the two best ways to understand firsthand the brutality of the regime is to visit S21, or Tuol Sleng Prison in southern Phnom Penh. Originally a high school, it was turned into a secret prison where an estimated 17,000 prisoners were detained, tortured, forced into false confessions against their family and friends, then sent to be executed.

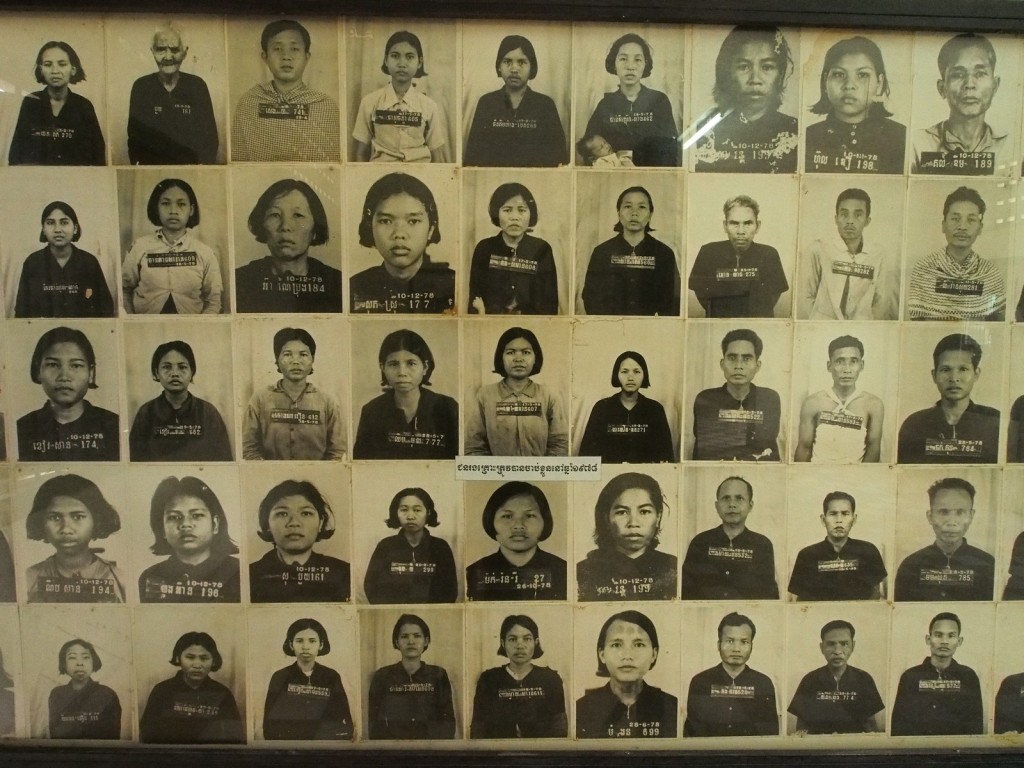

The Khmer Rouge, like the Nazis, kept detailed records of their crimes. Every prisoner was photographed on arrival and made to write a detailed autobiography, which was carefully filed with copies of their eventual confessions. One of the large three storey buildings is contains room after room full of the photographs of those held and killed there.

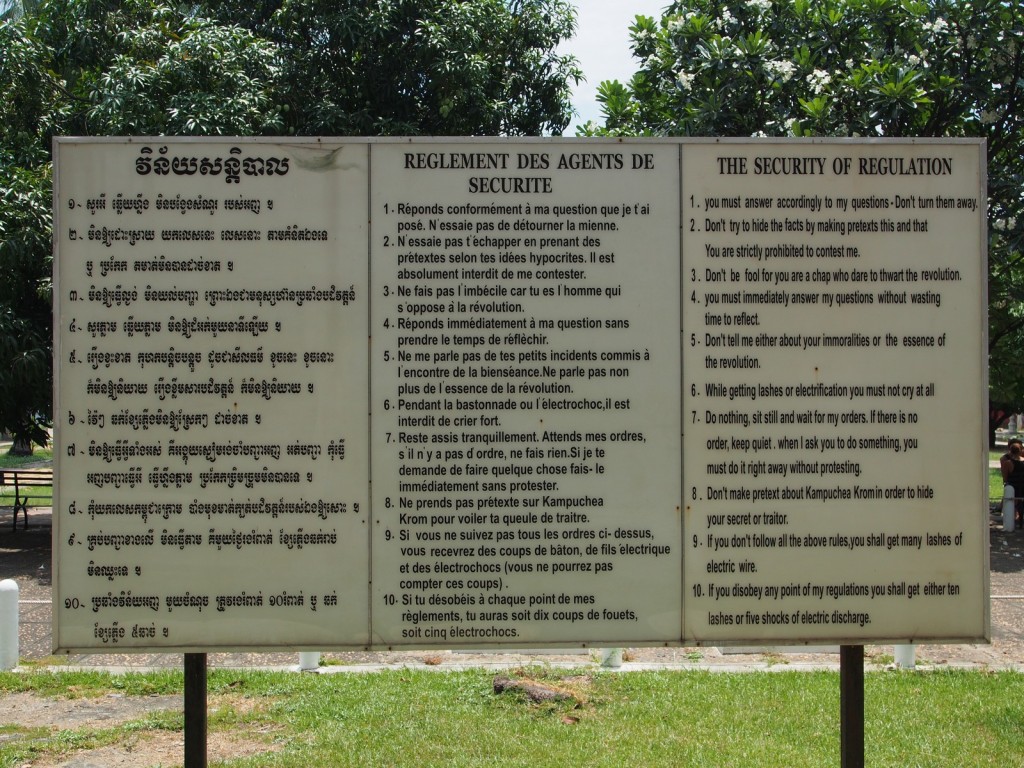

The prison rules make for sobering reading.

One of the buildings housed cells, crudely constructed from brick or timber. Some cells were less than a metre wide.

Barbed wire was strung across the balcony to prevent detainees committing suicide by jumping.

Another building had the individual rooms for more important prisoners, such as high ranking regime officials who might have conspired against the regime. The rooms might be better but their fate was not.

The methods to extract confessions included starvation, beatings, electric shocks, waterboarding, pulling nails, and cutting with knives while pouring salt or alcohol on the wounds. These ‘confessions’, usually that the prisoner was a CIA or KGB spy, had to include a list of names of those who had conspired with them – all of whom would subsequently suffer the same fate. It’s a sobering experience, especially with the firsthand accounts, photos of the dead, and paintings of the methods of torture that I did not photograph.

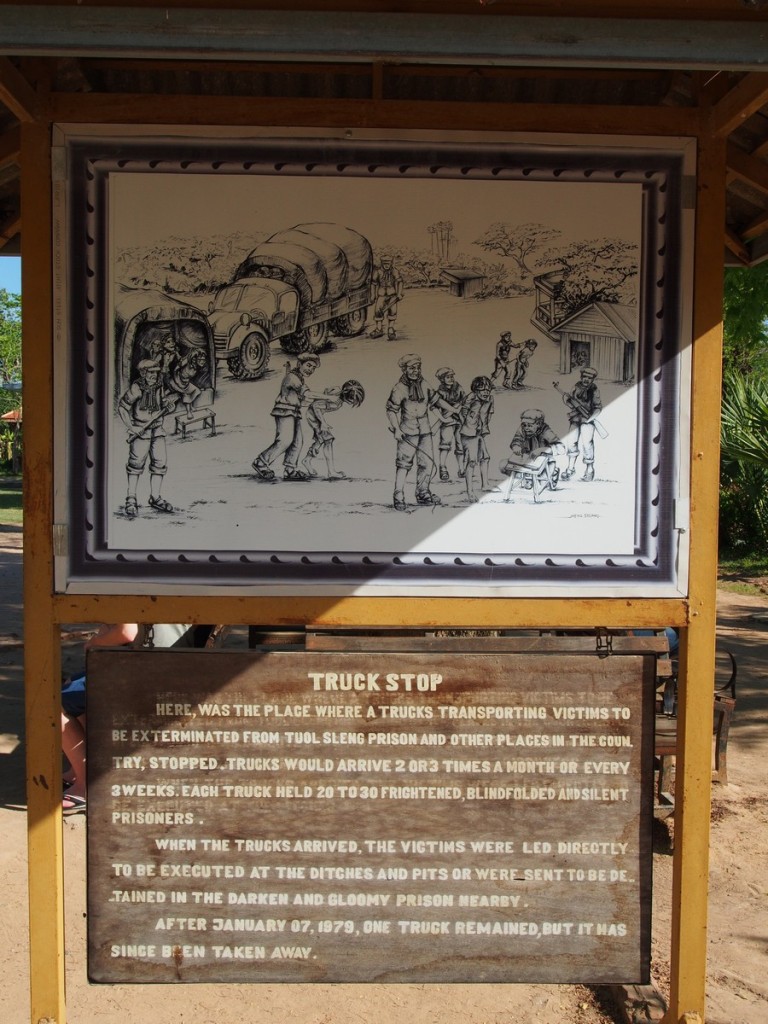

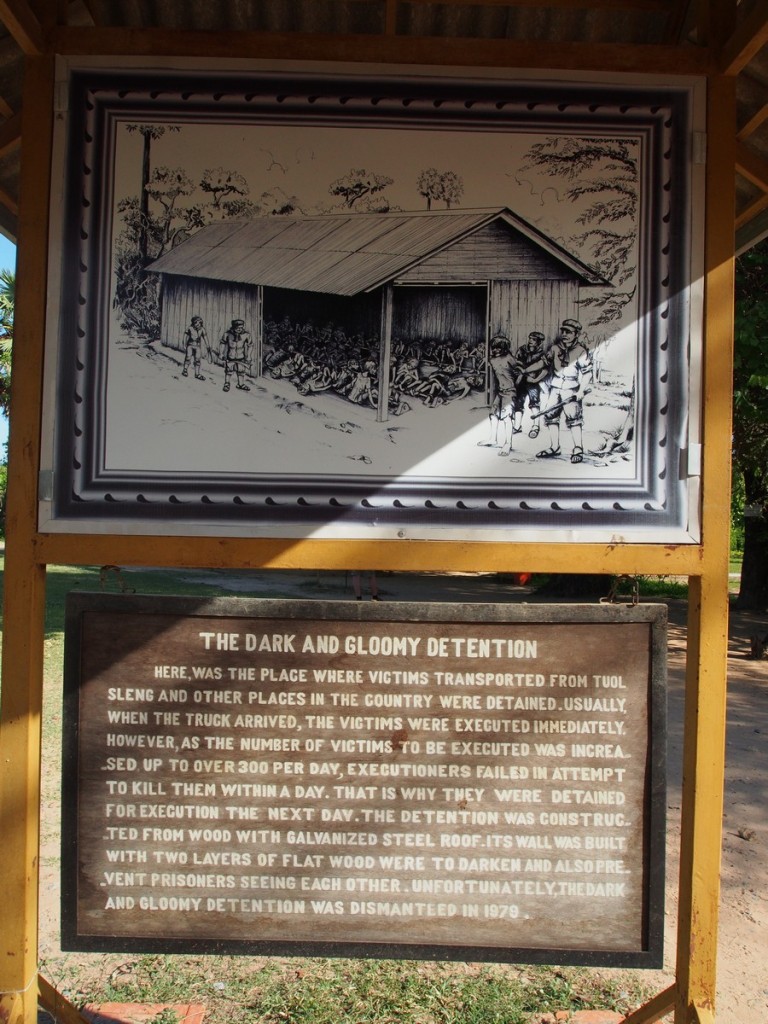

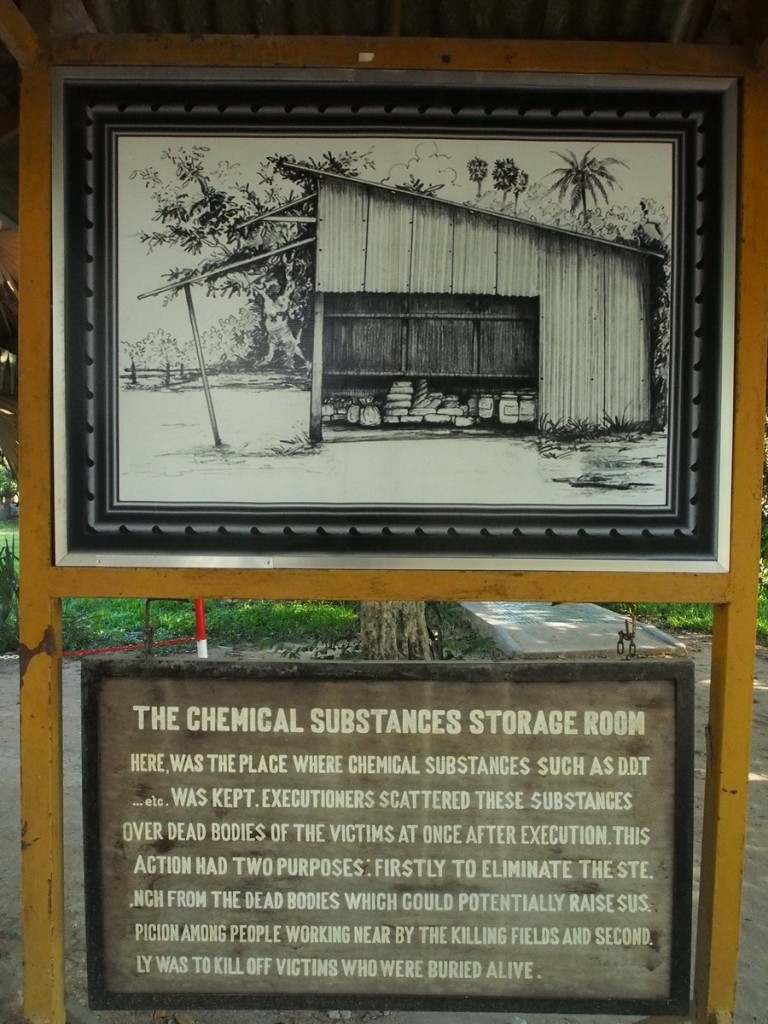

The second way to comprehend the genocide is to visit the Killing Fields of Choeung Ek, around 15km south of the city. It was here that the prisoners from S21 were sent once they had confessed. They were taken to mass graves and bludgeoned to death – bullets being too expensive.

There is an excellent audio-guide with first-hand accounts, that helps bring meaning to the relatively plain site. This makes it a peaceful place now, with all visitors lost inside the headphones with their thoughts. The dominant feature is the central Buddhist stupa – but we’ll come back to that.

Much of the site is left to the imagination, as the original rudimentary buildings are long gone.

Then you reach the site of the first mass grave, one of 129 here.

The holes around the area drive home how many pits there were.

Only about one third of the graves have been exhumed, and of those only the large bones such as skulls were removed – meaning that every day, bones, teeth, and scraps of clothing surface through the dirt. I can’t even begin to describe my feelings here.

It’s not the worst of the horrors though. Babies were plucked from their mothers’ arms, and had their brains bashed out against large trees. They were then thrown into the pit, and their mothers soon followed.

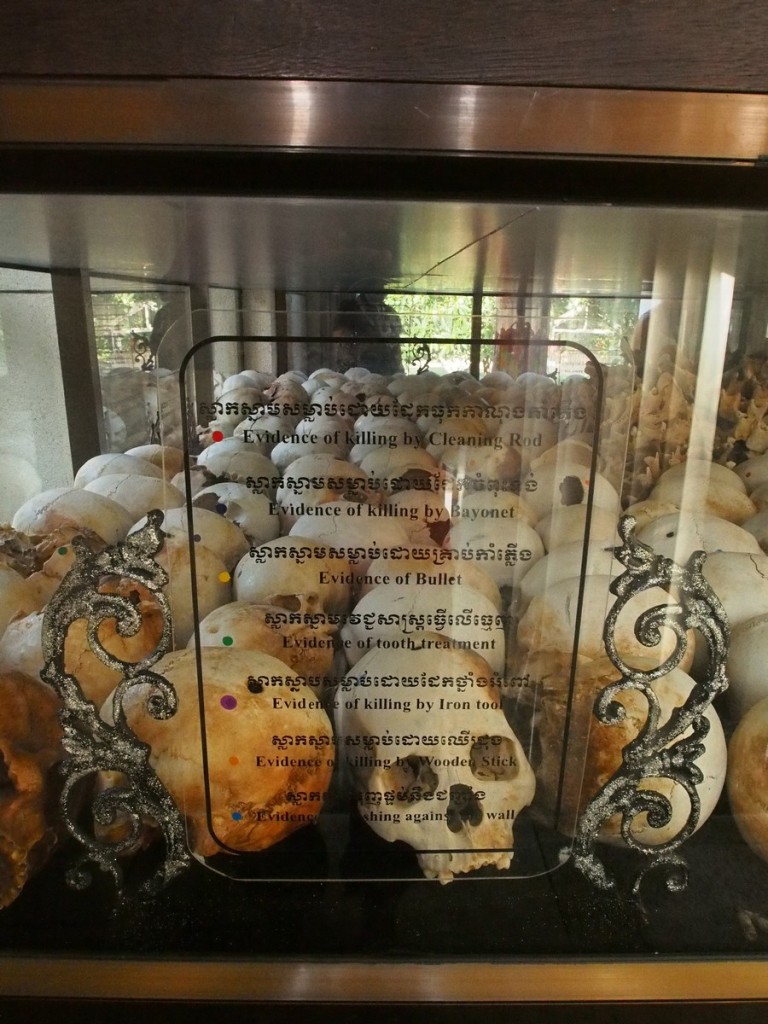

Finally, returning to the stupa at the beginning – it was built to house the remains of the 8,985 bodies exhumed from the graves, as a memorial.

The best estimates are that some 17,000 people were killed here – one of twenty thousand mass grave sites throughout the country. The nature and extent of the senseless brutality displayed at these two sites is nothing short of extraordinary.