Approaching Shiraz in Southern Iran, you enter the heartland of the ancient Achaemenid Empire. At its peak, it stretched over a demesne as far west as the Balkans and Eastern Europe, south as far as Egypt and Sudan, north to the Caucasus and Central Asia, and east to the Indus Valley including parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan, it was the first truly multicultural empire. Dozens of kingdoms were absorbed into the empire by its greatest king, Cyrus the Great, and were allowed to keep local religions and customs – as long as tribute was paid in both gold and soldiers. It is perhaps best known in modern culture from the film 300, depicting the Battle of Thermopylae. The empire lasted from the 6th Century BC until its destruction by Alexander the Great in 330 BC. What remains, particularly at Persepolis, are some of the most important and impressive archaeological ruins in the world.

Our first stop on the road was the ancient capital of Pasargadae, dating from 546 BC. Far less remains here then at famed Persepolis, making it an ideal introduction to the ruins – it would have been disappointing to have visited it afterwards. The most important structure here is the tomb of Cyrus the Great himself: a fairly plain, unimposing structure for such an important historical figure – but that may be the reason it survived the ages so well.

The remains of the summer palace are nearby, mostly foundations with enough standing columns and carving to give a sense of the scale and grandeur – but still leaving plenty of work for the imagination to do.

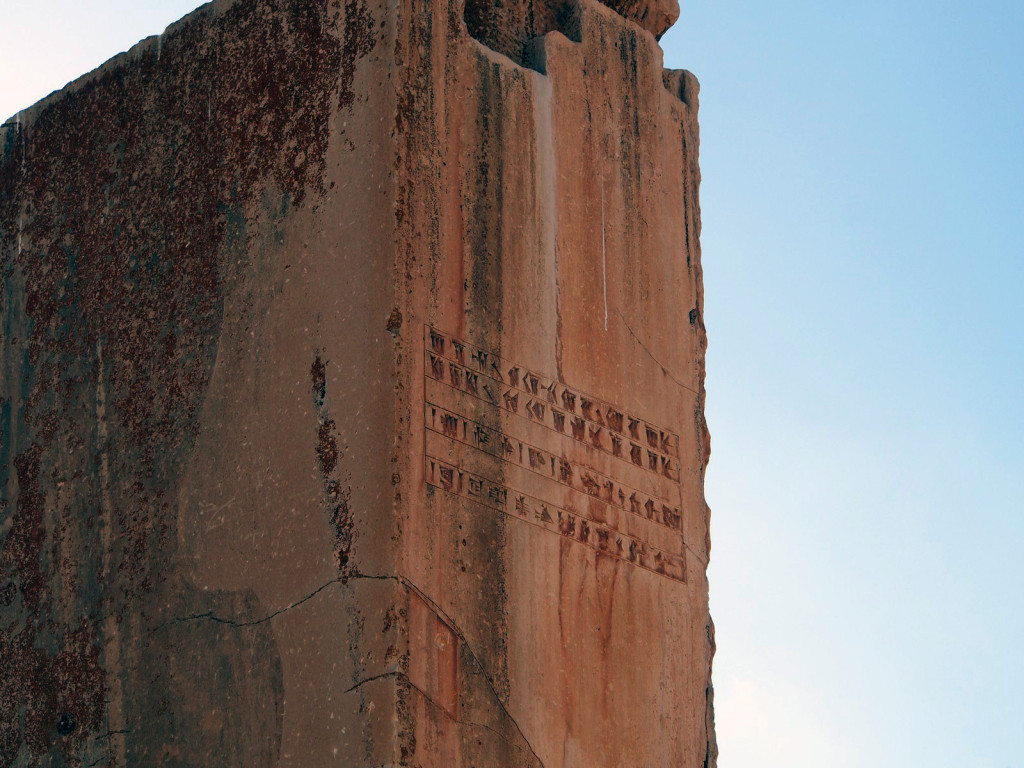

On a nearby hilltop are the remains of a fortress – only the large slab walls standing firm against time and the elements.

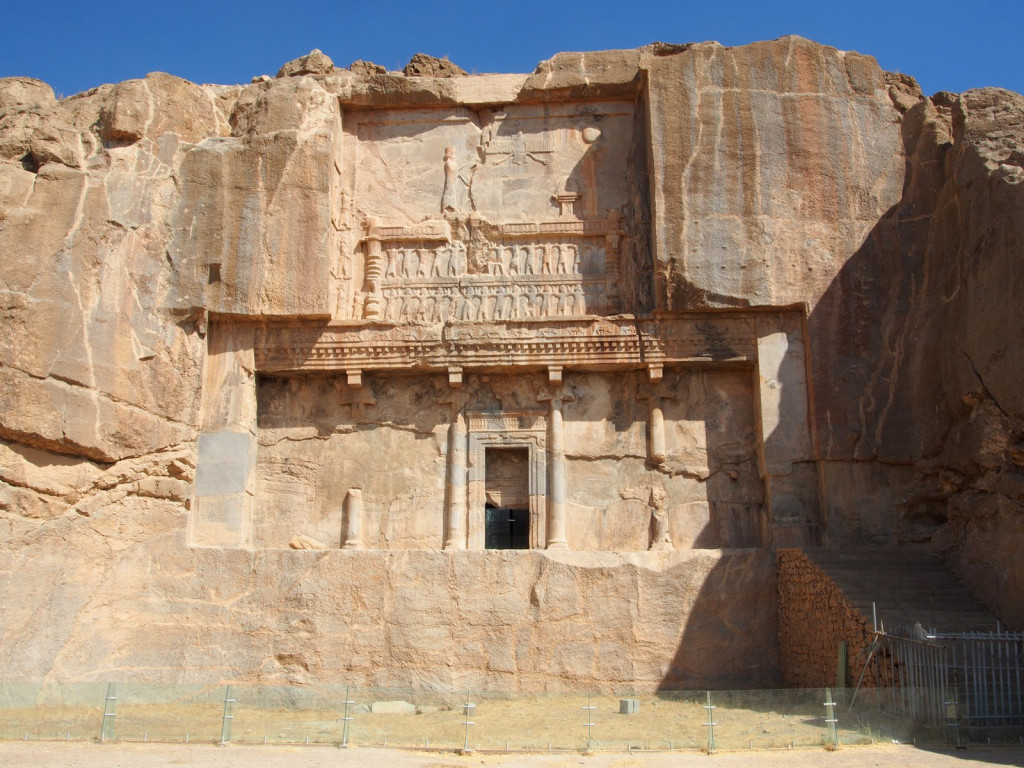

Fifty kilometres further southwest, you reach the fringes of Persepolis, with two rock-carving sites. Naqsh-e-Rostam contains the cliffside tombs of four of the most important kings of the Achaemenids – Darius I and II, Xerxes I and Artaxerxes I. They’re huge, monumental sections of the sheer rock wall that have been carved out in bas-relief, including a small funerary chamber in the centre. They’re visible from over a kilometre away on the nearby highway, and loom over you as you approach.

Each tomb is carved in a similar pattern, with the symbol of Ahuramazda, the god of Zoroastrianism at the top, then the king being supported by his subjects from different nations, then faux-columns flanking the entrance to the ossuary.

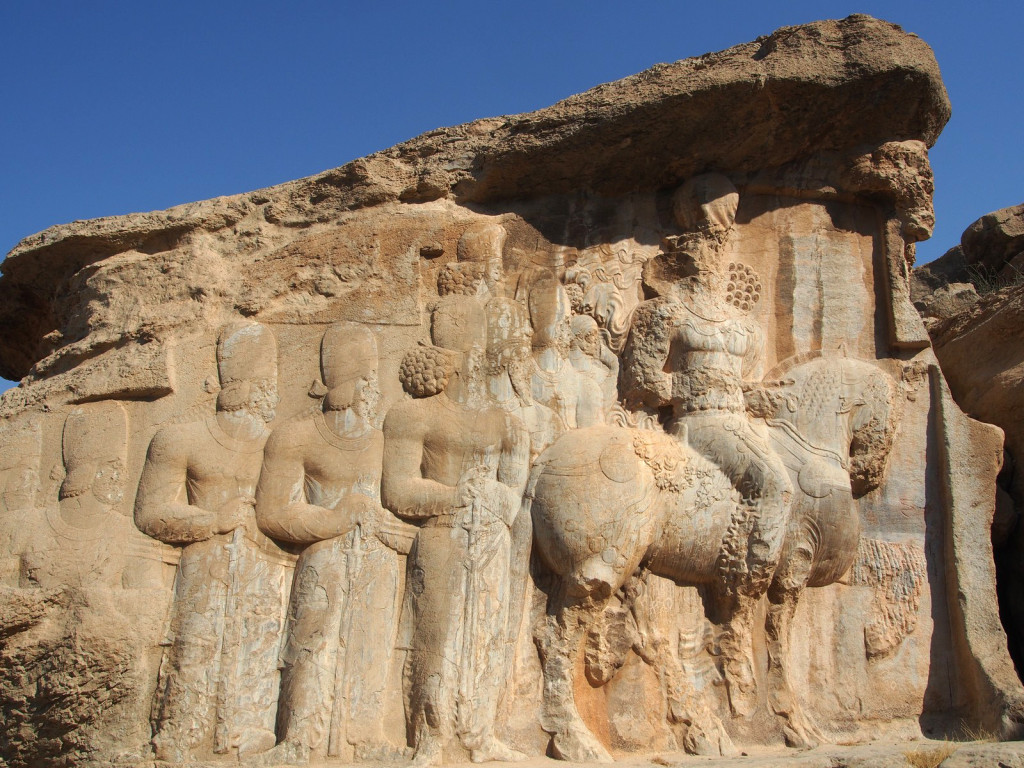

There are also a number of fine bas-reliefs dating from the later Sassanid period (2nd and 3rd Century AD), depicting military victories and coronations – seeking legitimacy by linking themselves to the earlier empire.

Nearby at Naqsh-e-Rajab, hidden in the folds of a hillside, are more finely detailed Sassanid carvings.

Finally, we arrived at Persepolis itself. Built as a ceremonial palace, mostly for receiving the annual tributes from subject nations, it was designed from the outset to impress foreigners – and still holds that power today. Elevated on a flat terrace, half excavated from the mountainside and half built up from the plain below, it’s a long walk through the scorching sun to the site, giving you time to appreciate its scale.

Access to the palace is, as it was 2500 years ago, via the grand staircase. Its shallow steps allowed nobles in long robes to climb gracefully.

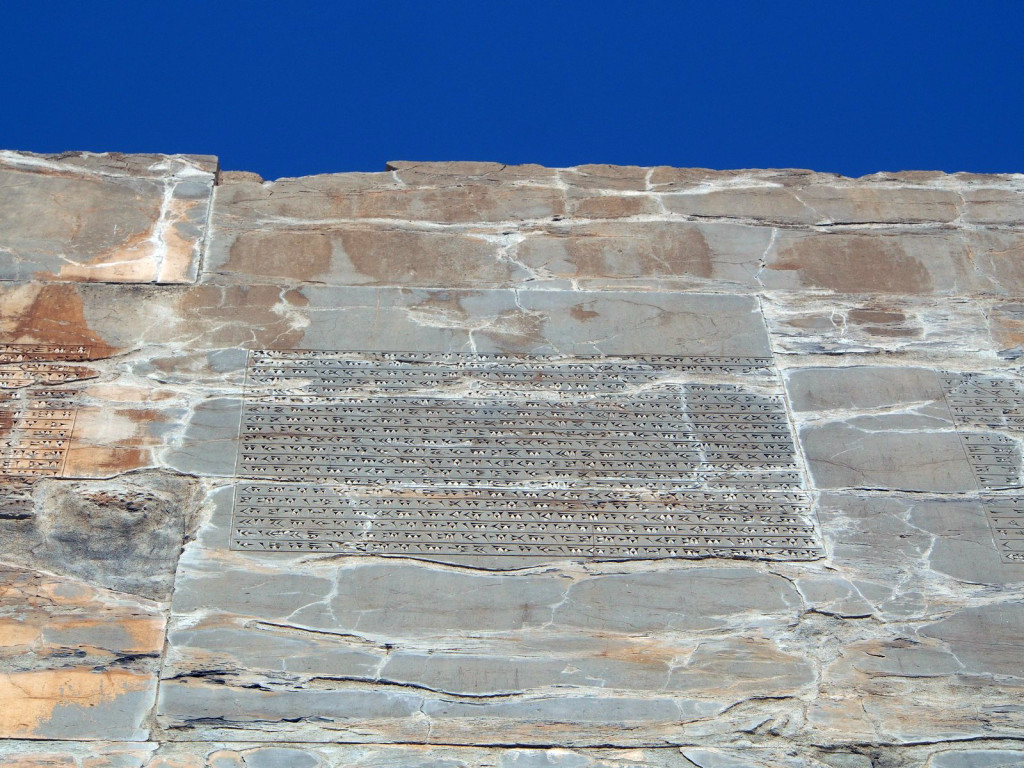

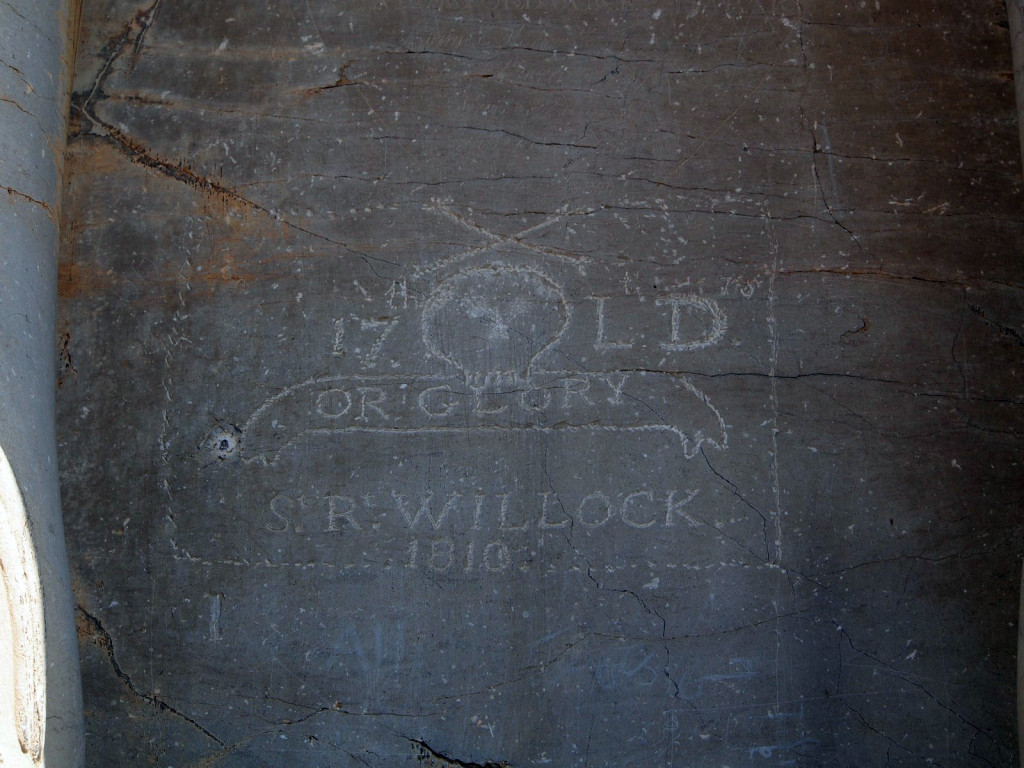

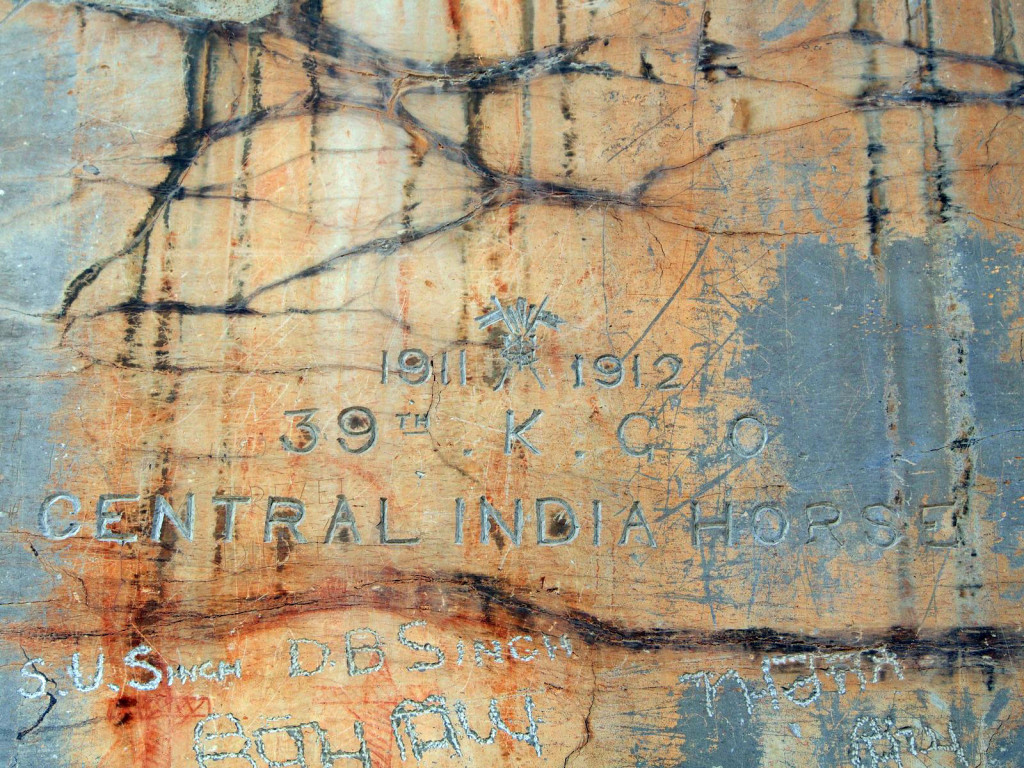

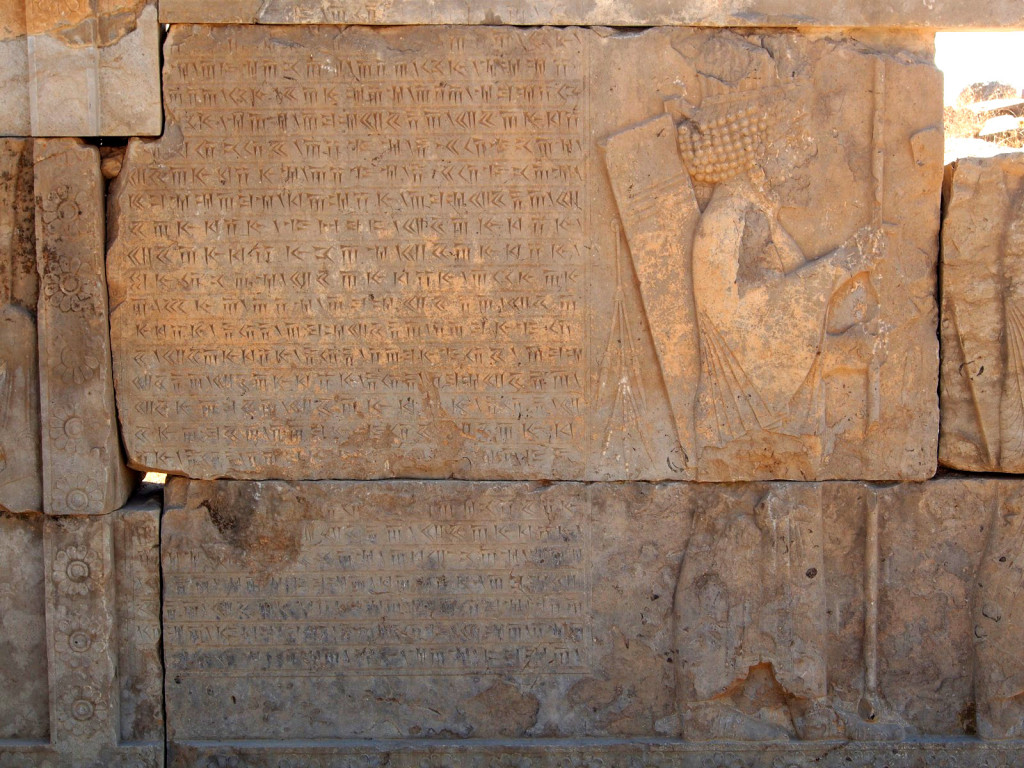

One of the most impressive remaining features, the Gate of All Nations, is the formal entrance to the complex. Protected at each corner by enormous mythical guardian statues, it is marked with both an ancient cuneiform inscription by its builder, Xerxes I, and more modern graffiti.

Just south of the Gate of All Nations is the largest building at Persepolis, the Apadana Palace, used for official audiences.

The most famous part is the eastern staircase, where extensive detailed carvings show Persian and Median soldiers, as well as motifs symbolising royal power and legitimacy.

Other carvings depict representatives from the subject nations, bringing tributes from each of their countries – ranging from horses and chariots, to camels, fabrics and precious metals.

There are a number of other ruined palaces and halls scattered nearby, some richly decorated with more carvings and bas-reliefs.

Also around are shattered statues and column-heads.

The treasury was once almost as large as the Apadana palace, although now only the foundations remain. It is said Alexander the Great needed 3,000 camels to carry off the contents when he sacked the city. One of the most important carvings is here, depicting Xerxes receiving his just tribute – it was most likely moved by a subsequent king for political reasons.

Climbing the hill behind the complex gives both a panoramic view over the ruins, and access to two more cliff-carved tombs, likely those of Artaxerxes II and III.

Redescending to the complex, at the rear is the Palace of 100 Columns, with more carvings depicting the King battling various beasts and monsters.

Thoroughly impressed (and more than a little sunburnt), we continued on to Shiraz.